Who would have thought that embroiderers and knitters/crocheters -- who are needleworkers too -- are at the forefront of an industrial

revolution? In fact we are about 450 years ahead of the pack. Amazed? Read on.

Recently, mainstream media reported, thoroughly impressed, on OpenDesk --

a “revolutionary” approach to manufacturing wooden furniture, and even frame

houses. The only thing that gets shipped

is information.

Here’s how it works. A designer using a computer creates a blueprint. The

drawing is sent over the internet to a workshop somewhere near the customer.

Here the design is milled by computer-controlled

equipment to produce parts which the customer will assemble.

This process saves money by eliminating unwanted stock. The environment

benefits. We are likely to encounter

more such excitement as 3-D printing pushes into homes and workshops near

us.

For those of us who use needles this is, frankly, so much old hat.

Substitute the word “pattern” for blueprint and “artisan” for computer and you

will instantly see what I mean.

Patterns for needlework have been around

since the 16th century, made possible through that earlier

disruptive technology, the printing press.

Weighing less than goods, patterns were carried across distance to

needle-wielding artisans, who fabricated what clients wanted using materials

available locally.

|

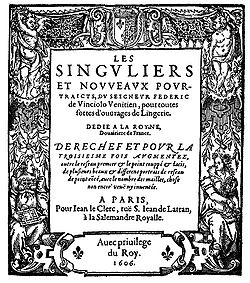

| A pattern book dating from 1606 |

And while transferring patterns for making furniture over the Net may be

“cutting edge”, transporting handwork

patterns via the internet is quite routine.

Contemporary needlework designers have been quick to embrace computers and internet technology, selling patterns via Etsy and Ebay for the best part of a decade.

Contemporary needlework designers have been quick to embrace computers and internet technology, selling patterns via Etsy and Ebay for the best part of a decade.

Clearly, how modern or revolutionary a

process is, depends on the direction you are looking, forward or backward.

And who’s doing the looking, men or women, young or old. So squinting through

the eye of my needle, it all looks a bit déjà

vu.

Just thinking about it, I experience even more déjà vu.

Beyond knowing how to wield a needle and where to place it, needleworkers

acquire two other skills. Using a pattern

implies being able to interpret codes. These codes may be in the form of a chart or the

*k1 p2* instructions in knitting, for example.

Moreover, needlework buffs replicated directions flawlessly and

consistently for yards and meters, and for days on end without flagging. Kind

of like, well, a computer? Precisely.

These aspects of needlework have been recognized in the term “numerical

needlework” that appeared in an article about

number crunching, repetitive computations done by hand in the days before

electronic computers. And who were the “human computers” with the skill to

replicate calculations ad infinitum? Yep, women. In fact way back when, computing power was measured in kilo-girls. I kid

you not.

During World War 2, most of the top-secret code-breaking computational work

done at Bletchley Park in England was done by women.

|

| Women working with the Bletchly Park computer in 1943. |

So it should be no surprise that creating

a handwork design is similar to designing a computer program, and charting a pattern or rendering it in letters

and asterisk codes, is, well, analogous to programming for a computer, albeit a

human one.

This brings to mind another intriguing question. Are needleworkers – today

primarily women - at an advantage when it comes to program design and coding

because of skills they honed through needlework? Well

the jury is still out on that one.

Still, computer history considers Ada Lovelace, the first program analyst. Given

her socio-economic status, it is probable that in addition to studying maths and

science she also did needlework, proving handwork needn’t hold back female

development. And to cite a more modern

equivalent there is Admiral Grace Hopper, developer of computer

language Cobol, who crocheted

and did needlework avidly.

The questions around value of embroidery as a way of teaching intrinsic skills is certainly worth exploring. Maybe it’s time to apply the logic in Malcom

Gladwell’s latest book, David and Goliath. He maintains that what is commonly perceived

as a disadvantage may, in fact, be an advantage when viewed from a different

perspective.

But how do we embroiderers get non-stitchers to focus on the valuable, positive qualities

that needlework fosters - persistence, care, and accuracy - rather than focus

on the perceived negatives of the needlework process – repetition and the end-product, which, when a tablecloth, a scarf, or pot holder, may be out step with fashion? That is really

difficult in an age when “instant” gratification is reinforced by faux

self-expression ensconced in fad. Still it is worth trying.

One could argue that persistence, care and accuracy are also stimulated by

learning to read music - another form of

pattern - and to play an instrument. Why in today’s world is music more broadly

accepted than needlework as a form of self expression and a mark of cultural

sensibility?

It may have something to do with the aspect of “hand” in handwork. East and West seem to agree that modernity is

associated with using machines of all sorts whether they sew or print. Both Chinese and American children are losing handwriting skills as computers march

into classrooms, for example. I can understand that. When it comes to writing,

give me my computer.

But I intend to do my bit to align the PR image of needlework with the 21st

century technology. I am going to stop

saying I do embroidery. The next time

someone asks me what I am up to these days, I may just say, I’m coding. Well I

am, encoding in thread. A rose by any

other name is still a rose.

Or are you deciphering? Moot point.

ReplyDeleteLove this - very perceptive, as well as being amusing and to the point.

Tell me more about Gladwell's book. I haven't heard of that one but have read Blink and Tipping Point and have, but not yet read, Outliers.

Cynthia, for more on the Gladwell book have a look at this:

Deletehttp://www.theguardian.com/books/oliver-burkeman-s-blog/audio/2013/dec/28/malcolm-gladwell-david-goliath-podcast